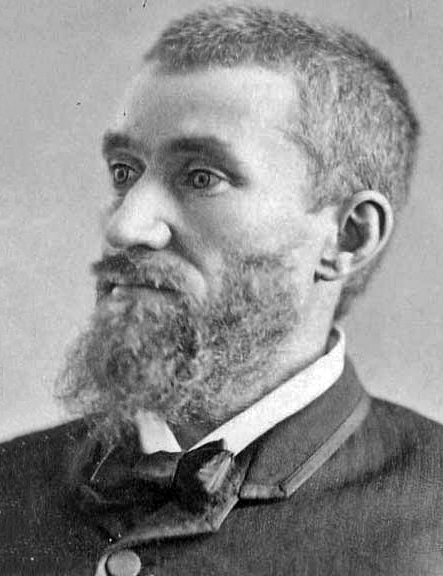

“I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad. I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad. I am going to the Lordy, Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lordy! – From a poem written by Charles Guiteau on the morning of his execution.

Charles Julius Guiteau was born in Freeport, Illinois, the fourth of six children of Jane August (Howe) and Luther Wilson Guiteau. They were of French Huguenot ancestry. In 1850, the family lived in Wisconsin before moving back to Freeport.

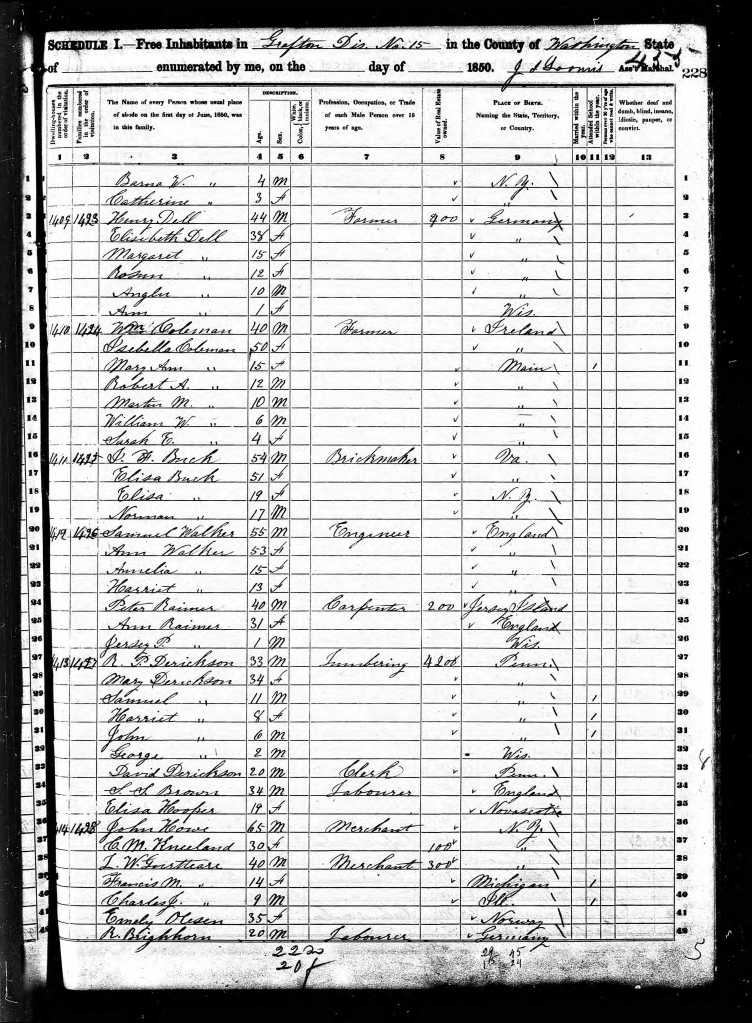

It’s not clear to me what the situation is on the 1850 census for Grafton, Wisconsin. Guiteau’s mother died in 1848, so on this census, he’s living with his father (last name spelled Gertteare by the census taker) and his older sister Frances. Also listed under dwelling number 1414 and family number 1428 are John Howe, a merchant aged 65, a woman named C. M. Kneeland, aged 30, Emily Olsen, 35, an immigrant from Norway, and a 20-year-old laborer, R. Brighhorn, from Germany. I suspect this is a boarding house run by Howe.

The neighborhood is made up of 40% immigrants, mostly English or German, and is working class (laborer, brickmaker, carpenter, etc.).

Later life

Guiteau lived a life of failure:

- Failed to gain admission to the University of Michigan.

- Failed to complete a program in French and Algebra undertaken to increase his chances for college admission

- Joined the Oneida Community, a utopian religious sect founded by John Humphrey Noyes, and failed to impress the members. Despite the “group marriage” tenets of the group, he was generally rejected and left the group.

- Started a newspaper which failed.

- Returned to the Oneida and was rejected again and left again. They called him “Charles Gitout.”

- Sued Noyes for payment for work he claimed to have performed. His father, who thought him insane, wrote letters in support of Noyes.

- Worked as a law clerk in Chicago and somehow passed the bar exam, but failed as a lawyer.

- Moved to New York City to avoid collectors and became interested in politics. Supported Horace Greely, who was badly defeated in the election of 1872.

- Wrote a religious book called The Truth, which was almost entirely plagiarized from Noyes. At this point, he felt he was to emulate the Apostle Paul and “preach a new gospel.” He went from town to town doing so.

- Moved to Boston but had to leave owing money and was suspected of theft.

In 1880 he supported Ulysses Grant for election to a third term as President. He wrote a speech supporting Grant. After James Garfield won the Republican nomination, he rewrote the speech – the rewriting consisted of changing Grant to Garfield in the text and he delivered it twice. When Garfield defeated Winfield Scott Hancock in the election, Guiteau believed that his efforts were largely responsible for the results and that he should be rewarded with a consul position in Vienna, before deciding on Paris.

He spent the spring of 1881 in Washington, D.C., living in rooming houses, skipping out when the bill came due, and stalking the new administration to demand his reward. After asking Secretary of State James G. Blaine for an appointment one too many times, Blaine told him “Never speak to me again on the Paris consulship as long as you live!”

Guiteau now decided that Garfield was going to destroy the Republican party by ending patronage and that Vice President Chester A. Arthur would save the party. He thought of killing Garfield with a knife but stated “Garfield would have crushed the life out of me with a single blow of his fist!” So, he bought a .44 British Bulldog revolver and began stalking Garfield.

He decided against an attempt when he followed Garfield to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad station. Garfield was seeing his wife off to their vacation home in Long Branch, NJ, and Guiteau didn’t want to upset Lucretia Garfield who was in poor health. On July 2, 1881, Garfield returned to the station to join Lucretia in Long Branch. Guiteau shot him twice from behind and while surrendering said “I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts. … Arthur is president now!”

But Arthur wasn’t President yet. Garfield lived for 11 weeks before dying, killed by Charles Guiteau with an able assist from his doctors and their unwashed hands and unsterilized instruments. Dr. Ira Rutkow, author of A President Felled by an Assassin and 1880’s Medical Care, says “Garfield had such a nonlethal wound. In today’s world, he would have gone home in a matter of two or three days.”

The question of insanity was debated during Garfield’s trial. Guitea wrote to President Arthur asking to be set free as thanks for raising Arthur’s salary by promoting him from Vice President to President. He also claimed, “The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him.” He made plans for a lecture tour upon his release and was going to run for President in 1884. When the jury found him guilty, he told them “You are all low, consummate jackasses!” He accused Arthur of “basest ingratitude” for not pardoning him, but believed Arthur would pressure the Supreme Court to free him.

Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882. Part of his brain can be viewed at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

Other events of September 8, 1841:

Birth of Antonín Dvořák, Czech composer (Slavonic Dances; New World Symphony; Cello Concerto in B, Op. 104), born in Nelahozeves, Czech Republic (d. 1904)

Tomorrow – Resting by the Sea

Please subscribe to our newsletter to receive each day’s entry in your email box.

Sources

- Wikipedia.org

- Ancestry.com

- Onthisday.com

- Picryl.com

- Youtube.com